Why the Black Square

My grandmother said it best when she told me, at the age of 91, that “You will never have it ‘all figured out.’” This human life is an opportunity for continuous evaluation, re-imagining, and growth. I’m gifted with a “grammie” who is whip smart, and has a mind like a steel trap. She’s 93 now, and a couple of months ago we had a deep, and emotional hour-long conversation about Covid-19. I wanted to know if the quarantine felt anything like the restrictions put in place around WWII. It doesn’t. In her memory, the era of WWII was a time of solidarity, compassion, generosity, and unity. The enemy had a face, Hitler, and no one in Oregon, or America, wanted to be under his tyrannical rule. My teenage grandpa volunteered for the Navy, risking his life to protect his future family from living beneath a swastika flag.

He was a talented multitasker and held the position of navigator and gunner on a plane based on an aircraft carrier. His job in the US military brought my grandfather, and my teenage grandmother, from rural Eastern Oregon to places they’d never imaged. Including the deep south, where they were stationed in Mississippi.

I hadn’t asked my grandmother about her southern experience until recently. Frankly, she leans conservative and throughout my childhood memories I could recall unsettling comments that she had made about race. Her great grandfather was notoriously cruel to his enslaved people, and these attitudes can trickle through generations. How do I know this? My mom uncovered an article featuring an interview with one of his formerly enslaved women where she shared bone-chilling stories of her life. Even thus! I’ll admit it, I still wanted to remain willfully ignorant to my own grandma’s true feelings and ideas on people of color. As a deep exploration into my own (past, present, and future) relationship with racism in America, however, muting my DNA is not an option.

So I called her on the phone and simply (said with air quotes) posed the query, “Grammie, can you tell me about the Jim Crow era in the South and in Eastern Oregon?” Then my whole body cringed in anticipation for the answer. First, she didn’t know who “Jim Crow” was. So I awkwardly explained my perception of her history with systemic racism. She patiently listened, and then we spent two hours un-braiding my perception and her perception of… well… everything. With adult ears I was able to better understand the comments she had made in my youth; with adult speech, I could discuss and reason with her on awkward and hard topics.

I came away from that conversation glowing, because after sitting in judgement of my grandmother for three decades, I found that she was an ally. She deeply hurt for black women in the south, and earned truckloads of side-eyes and nasty remarks from other white women for yielding her seat on the bus to women of color who were more exhausted than she was (which was against the law). The stories go on, but those are for me and her.

She admitted her self-work wasn’t done. And neither is mine. Our family history in Oregon, and the US is long. I’m a twelfth generation American. My people came from Scotland and Northern England to North Carolina with a “grant” from King George to homestead and farm. The first to immigrate was my great (to the power of 11) grandpa, William Hunter, who’s children married people who’s people had been in the US since the 1600’s, farming in Virginia. We are a family of farmers and ranchers, right up to today. We are part of a system that has taken advantage of people of color, and it’s past time to recognize that, and have hard conversations about it. My mother’s uncovering of the details of our family history sent me into what I called a “complete white-guilt inspired breakdown,” but what my soul guide and dear friend, actor Kevin Kenerly, called “an awakening.” I guess you can have both, side by side. And I continue to slog through this work.

Will you do the work with me?

Of course, movements abound across America right now, but I’m talking about that ongoing inner work. That work to find our own humanity.

I’d like to share a few of the places that I have visited, and what/who I have listed to, read, and watched which has made an impact on me, and inspired me to think deeper and be better. I’m also acknowledging that these aren’t all resources specifically related to BIPOC social justice issues, but an array of resources for expanding self awareness and leadership skills.

Listen

The 1619 Podcast, Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell, Wolfpack by Abby Wambach, Unlocking Us: Brené with Ibram X. Kendi on How to Be an Antiracist, Code Switch, The Problem We All Live With, from This American Life, Marc Maron’s Interview with Stacey Abrams.

Visit

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, The Museum of the American Revolution, The Whitney Plantation, The Liberty Bell.

Read

Farming While Black by Leah Penniman, The Hidden Wound By Wendell Berry, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, How Not to Be a Hot Mess by Devon and Craig Hase, Untamed by Glennon Doyle, The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd, An American Marriage by Tayari Jones, Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge by Erica Armstrong Dunbar.

Watch

13th, 8:46, American History X, Do the Right Thing.

Talk

With your family, with your friends, with your partner. Have open, awkward, uncomfortable and hard discussions about racism in beekeeping, farming and ranching, and America. Work to uncover your own family history, and think critically about how your relatives benefited from systemic racism. Here is a guide to “rumbling” from Brené Brown that can be used to help guide these conversations.

If you would like more action items, I urge to to read the newsletter excerpt from the National Farmers Union below. I’m always proud to serve on the board of directors for NFU, but I’ve been especially proud of them in the last couple of weeks - naming racism in American agriculture and vowing to be part of the solution. And I can tell you - this isn’t just part of a new trend. We’ve been having some awkward, difficult, and purposeful conversations, and have been taking steps to understand and take action around racism in agriculture.

And finally - my answer to “What is with the black square on your Instagram?” On June 2nd, I posted a black square to purposely mute my Instagram page so the pages of people of color could stand out. A few of my POC friend’s posts came through the noise, but not enough - so I decided to share a few of my favorite accounts on my page for the rest of the week, June 3rd-7th. Then I decided to be quiet for a few days and just observe and listen.

I’ll be doing more of this in the coming days, weeks, and years. Observing, and listening. And as always, doing the work (that will never be done) to know better and to do better.

National Farmers Union Calls for National Effort to Address Racism

The killing of Minnesota resident George Floyd has spurred widespread outrage and pushed the United States towards a reckoning with its long and painful legacy of racism.

The agricultural industry is not exempt from critique; though 14 percent of U.S. farmland was black-owned a hundred years ago, decades of systemic discrimination and the abuse of legal loopholes has left black farmers with just .52 percent of the nation's arable land. This has robbed black communities of billions of dollars of wealth, a fact that many experts say has contributed to the modern racial wealth gap.

National Farmers Union (NFU), which has historically supported social justice movements including women's suffrage and the civil rights movements, redoubled its efforts to support racial equity and justice in light of George Floyd's death. ""If we stand idly by while our friends and neighbors suffer - as too many of us have done for too long - we are complicit in their suffering," said NFU President Rob Larew in a statement. "To overcome the terrible legacy of racism in this country, we all must reflect on our own privileges and prejudices, rethink our institutions, and demand structural change."

The organization has been sharing ideas for how individuals can fight racism in the food system. Here is a place to start:

1. Educate yourself about racism in agriculture. There are many excellent books on the subject, including Farming While Black by Leah Penniman, Freedom Farmers by Monica White, Dispossession by Pete Daniel, Black Food Geographies by Ashanté M. Reese, and The Color of Food. There is also a wealth of journalism on black land loss and structural racism, including these articles published by The Guardian, The Atlantic, ProPublica, and the Food and Environment Reporting Network.

2. Donate to organizations that support black farmers. Civil Eats has compiled a list here

3. Listen to black, indigenous, and people of color. Follow and amplify them on social media, feature them at conferences, give them the opportunity to hold positions of leadership.

4. Buy food from black farmers and other black-owned food businesses. You can find a list of black-owned grocery stores and farmers markets here, a list of farms and gardens here, and a list of restaurants here.

5. Vote for lawmakers who are committed to food justice.

6. Advocate policies that keep black farmers on their land.

NFU will continue to work towards justice in the food system - if you have thoughts or recommendations, please contact us here.

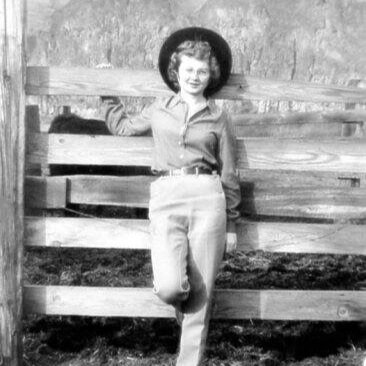

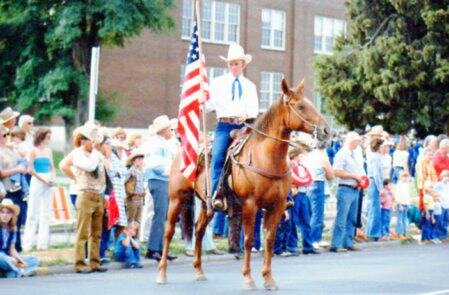

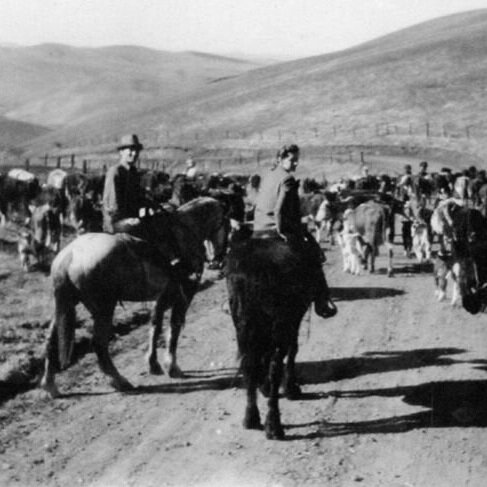

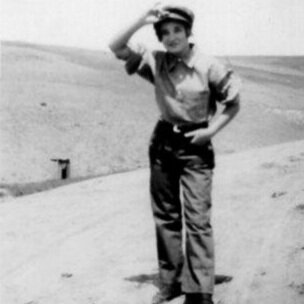

My Grammie (left) and other various members of my Eastern Oregon kin over the last few generations. I believe America is still in the Revolution that my ancestors fought to begin. Liberty and justice - for all.